Jack Harich's Bio

Hi there! Here's my CV. Below is my story. I'd love to hear yours sometime.

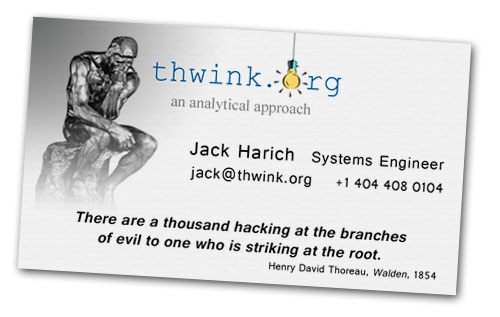

The short story is I'm a systems engineer and business consultant who's now a sustainability researcher. Here's the long story:

In 2001, after a career in small business management and consulting, I decided to say goodbye to solving business problems and hello to solving the most important problem in the world: sustainability. As a typical "call me in to fix your big problem" business consultant, I'd been fooling myself into thinking all those terribly important life-or-death business problems really were important.

They are not, compared to the health of the only biosphere we have.

That is the exact thought upon which I awoke. After that it was all about making up for lost time.

Once I committed, from the moment I began work on the sustainability problem full time there was an odd feeling of unease, of imbalance. Something was wrong but exactly what was not obvious. So with some apprehension I studied what people had been doing to solve the problem, book after book, article after article, conversation after conversation, organization after organization. It was a long lonely anxious slog, because I had no idea what lay beneath the surface and was working alone to avoid the groupthink trap.

Finally a theory of what was wrong began to emerge.

That's about when inside my head I drew a Nuts-O-Meter so I wouldn't go nuts myself.

The foreboding sense of unease, almost a black gloom, came from the way activists were so sure they were taking the right approach to solving the problem, BUT IT WAS NOT WORKING! They would try to push a solution through. It would mostly fail, like the way the US Senate voted 95 to zero in 1999 against signing the Kyoto Protocol on climate change. Then they would change something in the solution and try it again. It would fail too. From my point of view as a fresh outsider, five successive generations of solutions had now failed. ENVIRONMENTALISTS WERE TRYING THE SAME THING OVER AND OVER AND EXPECTING DIFFERENT RESULTS.

The foreboding sense of unease, almost a black gloom, came from the way activists were so sure they were taking the right approach to solving the problem, BUT IT WAS NOT WORKING! They would try to push a solution through. It would mostly fail, like the way the US Senate voted 95 to zero in 1999 against signing the Kyoto Protocol on climate change. Then they would change something in the solution and try it again. It would fail too. From my point of view as a fresh outsider, five successive generations of solutions had now failed. ENVIRONMENTALISTS WERE TRYING THE SAME THING OVER AND OVER AND EXPECTING DIFFERENT RESULTS.

That's what was wrong. It was also Einstein's fabled (but misattributed) definition of insanity. On the Nuts-O-Meter, the world as a whole was perilously close to going insane. This is a bit of a problem, because political insanity equals environmental disaster!

But environmental scholars, grassroot activists, and politicians like Al Gore are not insane. They are as dedicated and rational as you and me. They consistently believed that success was just around the corner, if only they could get people to believe their solutions must be adopted now.

But it wasn't working. So what was going wrong?

About this time The Death of Environmentalism memo came out in 2004. It got right to the point. In clear language page 6 said:

Over the last 15 years environmental foundations and organizations have invested hundreds of millions of dollars into combating global warming.

We have strikingly little to show for it.

From the battles over higher fuel efficiency for cars and trucks to the attempts to reduce carbon emissions through international treaties, environmental groups repeatedly have tried and failed to win national legislation that would reduce the threat of global warming. As a result, people in the environmental movement today find themselves politically less powerful than we were one and a half decades ago.

Yet in lengthy conversations, the vast majority of leaders from the largest environmental organizations and foundations in the country insisted to us that we are on the right track.

The authors, Michael Shellenberger and Ted Nordhaus, were seeing the same thing I was seeing: environmentalism is failing but it has its head in the sand. It insists all is well. We are doing the right thing.

Shellenberger and Nordhaus offered their blockbuster conclusion on page 10:

We have become convinced that modern environmentalism, with all of its unexamined assumptions, outdated concepts and exhausted strategies, must die so that something new can live.

There it was, in black and white. Environmentalism has failed. Environmentalism in its present form must die so that something new can take its place.

What will that be?

The search for an answer just about drove me nuts. To avoid falling into the same ruts and groupthink as others, I was working alone in deliberate isolation. It was a lonely struggle. Eventually, out of that struggle was born this insight:

Environmentalism is failing because it's taking the wrong problem solving approach.

Science was not science until it invented and adopted the Scientific Method. Business could not become business as we know it today until it invented and adopted double entry accounting, a bookkeeping system for calculating profits and solving profitability problems. Likewise, environmentalism will not become environmentalism until it invents and adopts a problem solving process that can crack the sustainability problem.

Now I had a strategy. By good fortune in my previous lifetime (before environmentalism) I was a business consultant. One of my specialities was process design and improvement. Plus I'm a systems engineer from Georgia Tech. So I designed a process from scratch to solve difficult social problems, especially sustainability. This became the System Improvement Process. It's what drives all the work at Thwink.org.

The heart and soul of the System Improvement Process is root cause analysis. That's because of this one all important principle:

The only way to solve a difficult problem

is to resolve its root causes.

This leads to another insight:

The exact reason environmentalism is failing is because its solutions do not resolve root causes.

Instead, they resolve intermediate causes. For example, more renewable energy or a carbon tax fixes the problem of too much fossil fuel burning. But what's the deeper cause of industrial growth? And what's the cause of the very strong pushback from industry lobbyists to solving the climate change problem? In developed nations, why is consumption per person growing far beyond what's actually needed for basic quality of life?

Questions like these reveal there are deeper causes at play. If we start at the symptoms of the problem and trace the causal chain down, down, down, we will find the root causes.

So I concluded that environmentalism in its present form was myopically fixated on resolving intermediate causes with superficial solutions. Until the movement changed to resolving root causes with fundamental solutions, it would perpetually be unable to solve the sustainability problem. How all this works is explained in this diagram:

What to do next?

That's where I'm stuck and need your help.

Here's what I've tried:

1. The System Improvement Process has grown into maturity. It now has 23 steps. It's been applied to the sustainability problem in an exhausting series of steps, models, simulation runs, analysis conclusions (especially the root causes), and 12 sample solution elements. All this has been written up into a 478 page book: Common Property Rights: A Process Driven Approach to Solving the Complete Sustainability Problem.

2. Even though I'm not a PhD, with the help of a few other dedicated analytical activists I've been lucky enough to get a paper published in a peer reviewed journal. This was Change Resistance as the Crux of the Environmental Sustainability Problem. It modeled the two main root causes of the problem.

3. This website contains 150 carefully written pages and dozens of PDF files about how to solve the sustainability problem using an analytical approach.

4. Just recently I've tried issue specific articles like this one on A Little Story about Corporate Dominance and the Occupy Movement.

Surely, I thought, if I publish this material to help environmentalists educate themselves about a more productive approach, they will pick it up. A few innovators and early adopters will see the merits of a root cause resolution approach. They will study it, start using it, and spread it to others.

But it hasn't happened. A few people are very interested. But we haven't gotten any significant organization to take up the concept.

So I was troubled all over again, just like when I started. That same sense of dread, of unease, crept over me. Why, why, why were people not seeing this approach could work?

That's where I need your help. I'm not a salesman. I'm a quiet introvert, a craftsman, an engineering type. My strength lies in analysis, not selling the ideas that come out of analysis.

Can you take the ball the rest of the way?

There's got to be a way we can get the ball rolling.

Jack's Real Bio

Role: The lead systems engineer and sustainologist at Thwink.org.

Nationality: United States. Raised on a farm in Maryland.

Qualifications: 20 years of small business and dot.com startup consulting, 6 years small business management, BS in Industrial & Systems Engineering; proficient in process design and improvement, problem analysis, software engineering and architecture, system dynamics, outdoor digital photography, the bamboo flute, art furniture and woodworking, and ultralite hiking.

Role: Jack's role is to initiate the concepts and strategies necessary to help those working on the sustainability problem approach the problem from a much more effective angle of attack, one hopefully an order of magnitude more productive.

Comment: "I believe that once environmentalists start using the same problem solving tools that others have long been using, they will be able to make strides so great they will astonish themselves. The absence of these tools can be explained by one simple fact: a very different type of person, on the average, is attracted to altruistic causes. As a result, they tend to be long on motivation and optimism, and short on the powerful productivity techniques known to business, science, engineering, and academia. It is these techniques and the strategies behind them that will make the difference in solving the sustainability problem."

Jack's personal web page is here.

Jack's

Story -

Jack is a bit of a thinker, a tinker and a better candlestick

maker. In 1970 he dropped out of Georgia Tech to run two businesses

for six years. The first was a startup bust, and the second

a big turnaround success. Then he moved into consulting and

finished up at Georgia Tech in Industrial Systems Engineering.

Many years consulting with small businesses, cooperatives,

distributors, and retailers were followed by a few years as

a furniture

artist. Shown is a shellback

rocker.

Jack's

Story -

Jack is a bit of a thinker, a tinker and a better candlestick

maker. In 1970 he dropped out of Georgia Tech to run two businesses

for six years. The first was a startup bust, and the second

a big turnaround success. Then he moved into consulting and

finished up at Georgia Tech in Industrial Systems Engineering.

Many years consulting with small businesses, cooperatives,

distributors, and retailers were followed by a few years as

a furniture

artist. Shown is a shellback

rocker.

On the side, he's been building The Tower since 1975. Here's what the tower looks like today. At the top of this page is what Jack looks like today, while below was long ago in the third grade. As both pictures show, he is forever young.

The life of an artist was followed by a return to consulting,

this time in the information technology industry during the

heady days of the dot com bubble. As they had been before,

Jack's specialties were a systematic analysis of a business's

or an industry's problems, formal process, and the crucial

role of information, communication, and collaboration in achieving

difficult objectives. Clients during this period included Delta

Airlines, the Center for Disease Control of Atlanta,

and Realm Technologies.

The life of an artist was followed by a return to consulting,

this time in the information technology industry during the

heady days of the dot com bubble. As they had been before,

Jack's specialties were a systematic analysis of a business's

or an industry's problems, formal process, and the crucial

role of information, communication, and collaboration in achieving

difficult objectives. Clients during this period included Delta

Airlines, the Center for Disease Control of Atlanta,

and Realm Technologies.

After finishing up with Realm Technologies (a high flying dot com startup), he looked around for the next challenging problem to solve, and decided that instead of solving more of the business world's problems, there was an infinitely more important problem that needed attention: the global environmental sustainability problem. If the problem is not solved then nothing else matters, so in mid 2001 he switched to working on it full time, and made it his life's work.

He immediately set up a six year plan. The first two years

were for becoming familiar with the problem in general. The

next two were for analysis and making an original contribution

that might make the difference. The last two years were for

starting to work elbow to elbow with others to help solve the

problem, while continuing his original work. There were two

top strategies: One was to deliberately work alone for the

first four years, so as to not fall into the same ruts and

group think of others, since 30 years of solution failure showed

that conventional wisdom was not working. The other strategy

was to create and follow a formal problem solving process that

fit the problem. The first version of this was created in a

few months and became the System Improvement Process. Amazingly

enough, the six year project plan came in on schedule. Now it's on to the fourth phase, which is continuing the analysis, publishing these concepts, and working with others.

He immediately set up a six year plan. The first two years

were for becoming familiar with the problem in general. The

next two were for analysis and making an original contribution

that might make the difference. The last two years were for

starting to work elbow to elbow with others to help solve the

problem, while continuing his original work. There were two

top strategies: One was to deliberately work alone for the

first four years, so as to not fall into the same ruts and

group think of others, since 30 years of solution failure showed

that conventional wisdom was not working. The other strategy

was to create and follow a formal problem solving process that

fit the problem. The first version of this was created in a

few months and became the System Improvement Process. Amazingly

enough, the six year project plan came in on schedule. Now it's on to the fourth phase, which is continuing the analysis, publishing these concepts, and working with others.

The optimist view: So far it has been a very difficult project, but the results of the first iteration of the analysis, and the reactions of those who have taken the time to read and understand it, are looking very promising.

The realistic view: Due to what appears to be strong paradigm change resistance, these ideas are languishing. They are dying on the vine.

Sigh....

Photo at top of page by Martha Harich on May 1, 2012.