Sustainability

We're going to define sustainability quite differently from normal definitions because the most popular definition in the world, the Brundtland definition of so called "sustainable development," is flawed. It's so flawed it should be tossed on the rubbish heap of history's biggest catastrophic mistakes.

First we'll give you our definition, followed by a look at why "sustainable development" is not just flawed. It was designed to deliberately lead problem solvers astray, because guess who "development" benefits most, even more than developing nations? Why large for-profit corporations, of course.

Contents

Why the popular definition of sustainability is flawed

How the flawed Brundtland definition came to be

Getting the definition right by getting our priorities right

Our definition

Sustainability is the ability to continue a defined behavior indefinitely.

For more practical detail the behavior you wish to continue indefinitely must be defined. For example:

Environmental sustainability is the ability to maintain rates of renewable resource harvest, pollution creation, and non-renewable resource depletion that can be continued indefinitely.

Economic sustainability is the ability to support a defined level of economic production indefinitely.

Social sustainability is the ability of a social system, such as a country, to function at a defined level of social well being indefinitely.

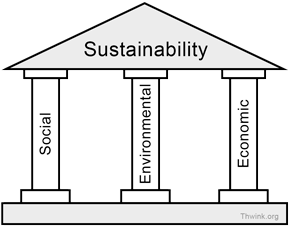

A more complete definition of sustainability is thus environmental, economic, and social sustainability. This forms the goal of The Three Pillars of Sustainability.

Why the popular definition of sustainability is flawed

The above definition of sustainability goes against the norm. The most popular definition of sustainability is that from the Brundtland Report of 1987, which said: 1

Sustainable development is development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs. It contains within it two key concepts:

The concept of 'needs', in particular the essential needs of the world's poor, to which overriding priority should be given; and

The idea of limitations imposed by the state of technology and social organization on the environment's ability to meet present and future needs.

The drawback to the Brundtland definition is it’s more inspirational than practical. It’s not precise and measurable, so no one can agree on what it means. This caused the definition to be plagued by controversy from the day it was published. The definition has also fallen into the trap of scope creep by including solving the global poverty problem. (This and the promise of development were included to bring undeveloped countries on board. Otherwise they were against solving what they perceived to be a problem created by developed countries.)

Should poverty really receive “overriding priority” over environmental sustainability? No, because if the environmental sustainability problem isn’t solved, then no other problem will matter due to catastrophic collapse. If the poverty problem isn’t solved, the world changes little. The poverty problem has existed for as long as Homo sapiens has. It’s nothing new. But the global environmental sustainability problem is new and threatens existence of our species. That’s why it deserves top priority.

Furthermore, “development” means economic growth to most nations, especially the developing ones. But that just makes the sustainability problem worse, since the economic system is already unsustainable. In theory, as Hermann Daly and others have suggested, “development” should mean both qualitative and quantitative growth. Qualitative growth (an increase in quality of life) can be very sustainable. But quantitative growth (economic growth) cannot be sustainable once it passes its limit, which it already has.

Meanwhile, "development" means sales growth for Corporatis profitis. Sales growth means profit growth. Short term growth in profits at the price of long term degradation of the environment is just fine with large for-profit corporations. After all, short term maximization of profits is their top goal. So the more corporations can push the Brundtland definition on the world, the higher their profits.

Unfortunately, that also means the lower the sustainability of society's actions.

Therefore the Brundtland definition is too flawed to use.

Here's the real surprise. Actually the Brundtland definition is not defining sustainability. It's defining sustainable development. What quietly happened long ago was the world's problem solvers redefined sustainability as sustainable development and then defined that. But sustainable development is a solution. It is not the problem to solve.

Thus the Brundtland definition is not only too flawed to use. It has defined the wrong problem to solve.

The right problem is the one in the definition at the top of this page.

How the flawed Brundtland definition came to be

The story of now the world's most popular definition of sustainability came to be (along with how it was flawed from the start) was told by Maurice Strong in his book Where on Earth Are We Going, 2000, pages 120 to 123. Speaking about the Stockholm Conference of 1972, of which he was secretary general, Maurice wrote that:

The biggest single threat to the conference was the ambivalence, even antipathy, that developing countries felt toward the whole issue of development.

From the beginning, developing countries had regarded the West’s concern with ‘the environment’ as just another fad of the industrialized countries; in their view pollution and environmental contamination were diseases of the rich, which could only divert attention and resources from their principal concerns: underdevelopment and poverty. They were understandably sensitive to the possibility that measures designed to protect the environment would impose new constraints on their development. Most of them would gladly exchange a little pollution for the benefits of economic growth. There was a growing movement to boycott the conference.

I knew the conference would fail if we couldn’t persuade the developing countries to take part, and I knew they’d never agree to come unless their concerns were addressed. The draft conference agenda I’d inherited didn’t even attempt to do so. On the contrary, it was heavily skewed toward issues affecting the more developed countries—air and water pollution and deterioration of the urban environment. If I was to get anywhere, I’d have to radically remake the agenda—which had already been accepted by the Preparatory Committee.

I went away to do some serious thinking. Then, when I was clear in my own mind what approach we should take, and with the astute guidance of the committee’s Jamaican chairman, Keith Johnson, I called its members together for a special meeting.

I laid out for them my revised agenda. The key concept called for a redefinition and expansion of the concept of environment to link it directly to the economic development process and the concerns of the developing countries.

This was a key error. It linked the global environmental sustainability problem to the poverty problem and the desire of less developed countries to catch up with the rest. Maurice continued:

Well, it sounds good. Nice linkage. But it means what? I could see their skepticism.

The basic thesis, I said, is simple: environmental and economic priorities are intrinsically two sides of the same coin. Of course, there will be conflicts and trade-offs in particular cases, but I pointed out that it was, after all, the process of economic development that has an impact on the environment, both positively and negatively. Only through better management, therefore, can the basic goals of development be achieved—to improve the lives and prospects of people in environmental and social as well as economic terms. My new agenda recognized that national priorities were dependent on the stage of development currently attained and would therefore vary. The key was to insist that the needs of developing countries would best be served by treating the environment as an integral dimension of development, rather than as an impediment.

While Maurice and the other planners had the best of intentions, not treating the environment as an “impediment” means it need not be the highest priority. This was the precise point in history where the proper priority of the environment over all else was rationalized away in a politically expedient tactical maneuver. Once a bargain like this is made, it tends to be difficult or impossible to reverse.

The Stockholm Conference planners went on to redefine sustainability as sustainable development and to define that as mentioned earlier. In doing so, they sowed the seeds of expectations that may have tipped the problem into insolvability. If most of the world expects and even demands economic growth as a priority over solving the sustainability problem, then how can the sustainability problem possibly be solved?

The early environmental movement never asked these questions, because most environmentalists are altruists. They want to help others. The poor need lots of help. I too feel for their plight. But unless we get our priorities right from the start, what we've done here is create a problem that's impossible to solve.

For me, and I hope you too, the right priority is the one embodied in the definition at the top of this page.

Getting the definition right by getting our priorities right

There is a bird's nest of interdependencies between the three types of sustainability mentioned at the top of this page. Social sustainability depends on economic sustainability, and vice versa. Social and economic sustainability depend on environmental sustainability. To a much smaller extent, environmental sustainability depends on economic and social sustainability. But the dominant dependency is that from a systems thinking viewpoint, the human system is a dependent subsystem of the larger system it lives within: the environment. Therefore, of the three, environmental sustainability must be society's top priority.

However, this priority is anything but clear in the standard definition of sustainability. This originated in the Brundtland Report in 1987, which defined sustainability as sustainable development, and sustainable development as "development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs."

Here's what Herman Daly, a widely respected ecological economist, wrote in Beyond Growth: The Economics of Sustainable Development, in 1996, page 1:

“Sustainable development is a term that everyone likes, but

nobody is sure of what it means. The term rose to the prominence

of a mantra—or a shibboleth—following the 1987 publication

of the UN sponsored Brundtland Commission report, Our Common

Future, which defined the term as development that meets

the needs of the present without sacrificing the ability of future

generations to meet their own needs.

“Sustainable development is a term that everyone likes, but

nobody is sure of what it means. The term rose to the prominence

of a mantra—or a shibboleth—following the 1987 publication

of the UN sponsored Brundtland Commission report, Our Common

Future, which defined the term as development that meets

the needs of the present without sacrificing the ability of future

generations to meet their own needs.

“While not vacuous by any means, this definition was sufficiently vague to allow for a broad consensus. Probably that was a good political strategy at the time—a consensus on a vague concept was better than disagreement on a sharply defined one. By 1995, however, this initial vagueness is no longer a basis for consensus, but a breeding ground for disagreement. Acceptance of a largely undefined term sets the stage for a situation where whoever can pin his or her definition on the term will automatically win a large political battle for influence over out future.”

Which is just what happened. Daly defines sustainable development as "development without growth beyond environmental limits." But economists like him were unable to get others to see things this way. He describes the dire results on page 9:

One way to render any concept innocuous is to expand its meaning to include everything. By 1991 the phrase [sustainable development] had acquired such cachet that everything had to be sustainable, and the relatively clear notion of environmental sustainability of the economic subsystem was buried under 'helpful' extensions such as social sustainability, political sustainability, financial sustainability, cultural sustainability, and on and on. Any definition that excludes nothing is a worthless definition.

Which is why we define sustainability as the ability to continue a defined behavior indefinitely.

Throughout this website, whenever we say just “sustainability,” we usually mean environmental sustainability, because if that is not achieved, then none of the zillions of other types of sustainability matter.

(1) The definition of sustainable development is from Our Common Future, by the World Commission on Environment and Development, 1987, p. 43.