Event Oriented Thinking

Event oriented thinking sees the world as a complex succession of events rather than as a system as a whole. An event is behavior that happened or will happen. Event oriented thinking assumes that each event has a cause and that changing the cause will correspondingly change the event. The rest of the system that produced the event need not be considered.

Why this concept is important

At first blush it seems that each event must have a cause. Otherwise, how could the universe function? Well, each event does have a cause. But that cause can have another cause, each event can also have more than one cause, each cause can have more than one cause, events can have probabilities rather than certainties, and event causes can change over time. Furthermore, in a complex system events or causes are usually part of feedback loops that cause effects elsewhere if the system is tampered with. Causal relations can be nonlinear, delayed, and highly non-intuitive. Putting all this together, one can quickly see that event oriented thinking is such an oversimplification that it is doomed to failure in all but the simplest or most familiar situations.

But event oriented thinking predominates in the human mind. Why? Because the brain and culture evolved to handle situations that were usually simple or familiar. Examples are fight or flight if you are threatened, plant food in the growing season so you can eat during the winter, harden the point of your spear so it works better, and if you don’t recognize someone as being part of your group, be suspicious. Event oriented thinking is even the basis of all logic: if A then B. Event oriented thinking is fast and efficient. Much of it is hard wired in our brains.

Only in modern times has event oriented thinking become a dangerous liability. Complex problems that require a system level of thinking have become commonplace. Event oriented thinking fails in any problem requiring understanding of a system's emergent properties. Most problems involving complex social systems cannot be solved with event oriented thinking, such as the global environmental sustainability problem.

The alternative

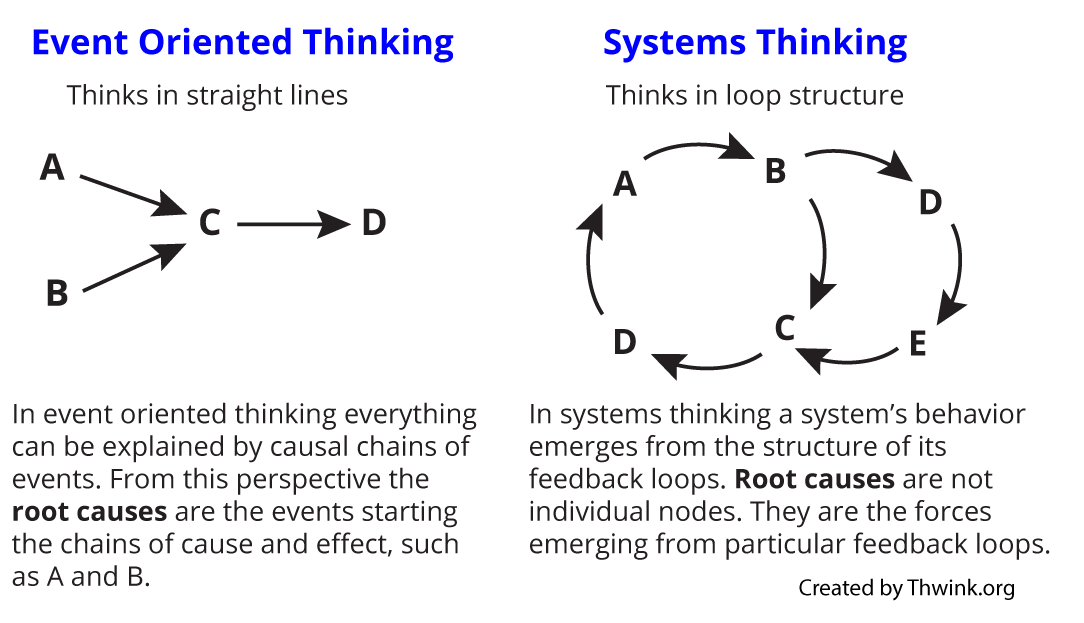

The alternative to event oriented thinking is systems thinking. The difference between these two ways of thinking is shown below:

Event oriented thinking predominates because it works on over 99% of the problems you encounter. It works because it's fast, simple, and easily learned.

For example, we learn that water evaporating from the land puts moisture in the air. This can turn into clouds that cause rain. That a straight line chain of events. The ultimate cause of rain is water evaporation. The intermediate cause is clouds full of moisture.

Systems thinking takes this much further. Rain falls onto the land. It sits there awhile, on the surface on in the aquifer, and eventually evaporates. That's an endless loop. The cause of interest could be anywhere on that loop, as well as the loop itself. The loop could be named The Force of Rain. The stronger the loop the more the rain, and vice versa.

When there's a shortage of rain the systems thinker looks at The Force of Rain loop and tries to determine why it's been weakened. If the loop involves a rain forest, then deforestation could be causing fallen rain to evaporate too quickly or too reflect more solar radiation, which would raise air temperatures and hasten evaporation. Any number of things could be weakening the loop.

This has been a simple example. Most people find it easy to follow because it's so close to event oriented thinking and is a familiar example. It's so simple it doesn't show off the power of systems thinking, so let's raise the bar to a better example.

The feedback loop contains only two nodes, birth rate and Population. The model also contains a constant, the fractional birth rate. This equals 1% per year. Population starts at 10 people. When the simulation model is run for 500 years, the exponential growth shown on the graph results.

Event oriented thinkers cannot look at a problem with exponential growth symptoms and rapidly find the loops causing it. Nor can they look at a system and spot the loops that have exponential growth potential. Thus when they encounter problems involving complex forms of exponential growth, they are helpless.

But not system thinkers. Once you become comfortable with thinking in terms of a system's structure, as defined by its important feedback loops, you will be able to solve problems that previously resisted your every attack, no matter how long you worked on the problem.

Sustainability is one such problem. Its chief symptom is exponential growth in undesirable environmental impact. So what are the important feedback loops causing that runaway growth? Going deeper, what are the loops that contain the root cause forces that are the ultimate changeable causes of the problem?